The troubled relationship between Hungary and Western Europe in the EU

A historical view on the undercurrent

The Hungarian Parliament: operational for 26 days during the 79 days of the Emergency Act.

Hungary and Poland blocked the adoption of the €1.8 trillion new long-term EU budget and the coronavirus recovery package, in the dispute over linking EU funds to the respect of rule of law. It is not the first time the accusations between Hungary and the Western European countries go back and forth. Within the EU the relationship between Hungary and Western Europe is far from easy. Hungary is accused of a democratic breakdown and reducing the freedom of the press. But at the same time the facts about Hungary are often distorted by Western media in order to put Hungary in the dock. Why?

I strongly suspect that there’s something fundamental going on in the undercurrent of the relationship. In this articel I will take you through history, for a better understanding.

The frame in the Corona crisis

First, let’s look at the very recent history. At the start of the Corona crisis, Hungary is portrayed as a country on the way to dictatorship. According to the Frankfurter Algemeine Zeitung “Hungary is sliding into dictatorship with Viktor Orbán”. “This week he will almost certainly acquire dictatorial powers” the Guardian writes on March 29, 2020. And in the Netherlands: “Orbán knows exactly how to abuse Corona” (Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, March 14, 2020). “Hungarian journalists fear for their future; as a critical reporter you quickly become a Corona collaborator” (Volkskrant, 28 March 2020). “Orbán uses the virus to build a totalitarian state.” (TV program ‘Buitenhof’, April 5, 2020).

What are the facts?

But what happened in reality? Dzsingisz Gabor has gathered the facts (see ‘Hongaarse ‘Corona’ Noodwet: Feiten & Fictie onder de loep‘). He is a former Dutch State Secretary and Hungarian by birth. The conclusion of his research: “The Emergency Act was in force for 79 days and was repealed on June 17. The legislation has not resulted in the inaction of the Hungarian parliament, nor in the imprisonment and silencing of opponents of the government as so-called ‘Corona collaborators’ “.

So what’s the problem?

Hungary is often attacked in the Western press for limiting its democracy. But does it explain why the West regularly puts Hungary in the dock, like this short illustration about the Corona crisis is showing?

I guess something far more fundamental is going on. With the ‘illiberal democracy’ Hungary is pursuing its own policy, a conservative one. My assumption is that Hungary and other countries in Central Europe no longer want to follow the politics of the West. From an earlier position of dependence, they now opt for sovereignty. And many in the West simply don’t like this. The result is an argumentative atmosphere.

This article will further substantiate this assumption. I will apply three perspectives I often use in my main profession (organizational psychology).

- The history: pivotal events and dominant stories that determine existing habits.

- The nature of the mutual relationships: are parties equal or one above the other?

- The undercurrent: thoughts, images and emotions that are often beneath the surface (or unconscious) and have a great influence on actual behavior.

On three places in this article I will give an intermezzo with these perspectives, as a wrap up.

History, relations and undercurrent

Dzsingisz Gabor in his article: “… this law has not led to the excesses that Dutch opinion makers warned against. The emergency law was not, as presented in our country, the monster that devoured Hungarian democracy. This legislation has helped to limit the number of very regrettable corona fatalities in Hungary so far to 58 people per million inhabitants.”

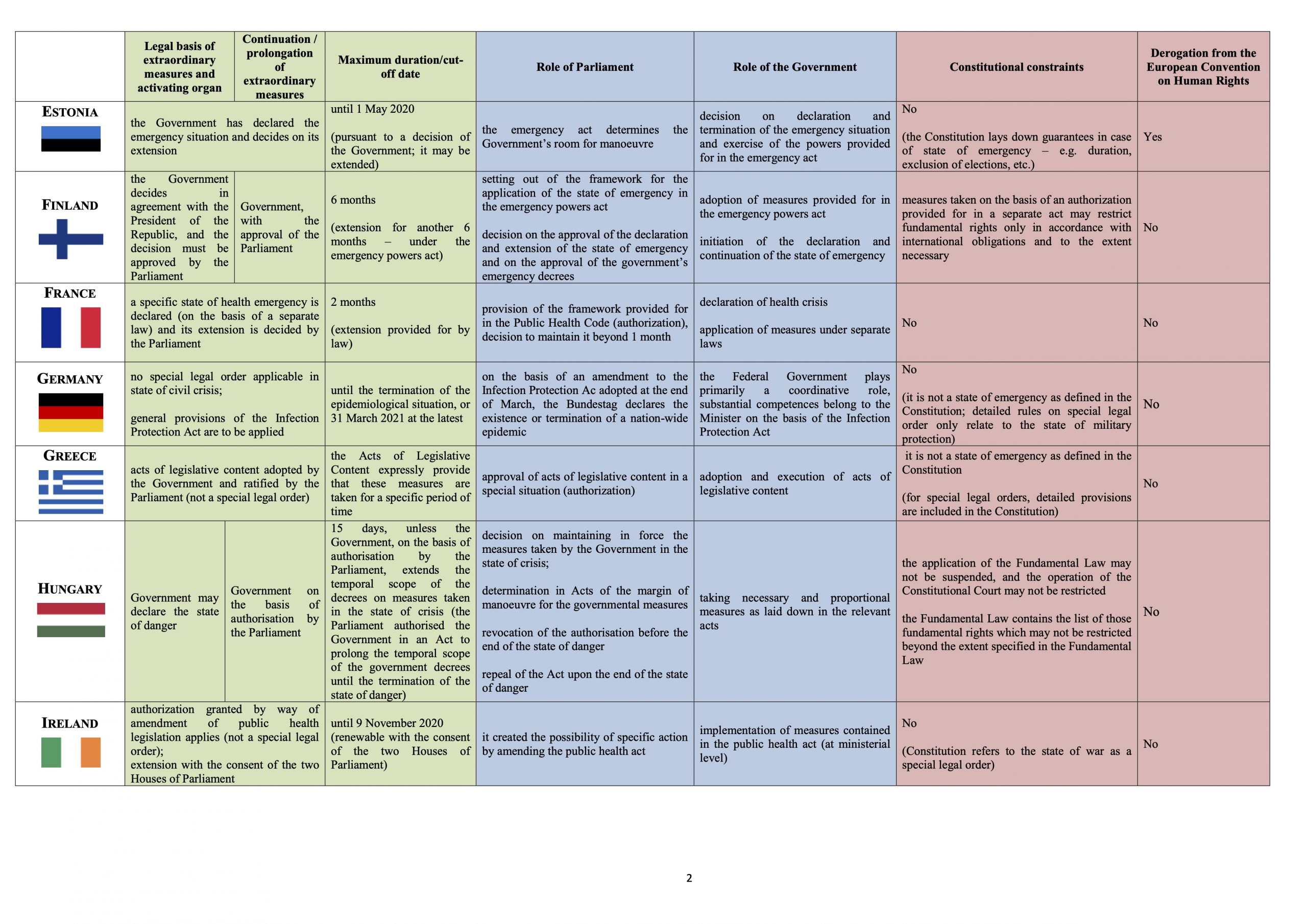

So at the beginning of the Corona crisis, the press seems to be sure that Hungary is sliding into a dictatorship. However, the press does not respond to counterarguments. For example, the Hungarian ambassador to the Netherlands András Kocsis speaks in the Dutch weekly Elsevier about “a lie campaign” and tells what he thinks is really happening in Hungary. And in the Nederlands Dagblad he writes “The new emergency law does not affect the rule of law in Hungary“. Furthermore, the Hungarian Minister of Justice Judith Varga publishes a matrix in which she compares the Corona legislation of Hungary with the Corona legislation in other countries in the EU.

Hungary has been put on the dock. But it is not justified by the facts in this case. Why put in the dock? Is it because Hungary scores low on democracy? In the Freedom Barometer Hungary ranks 32th out of 45 European countries. It is rated ‘partly free‘. ‘The Fidesz-led government has moved to institute policies that hamper the operations of opposition groups, journalists, universities, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) whose perspectives it finds unfavorable’ the Freedom Barometer writes. Italy is not far from Hungary at the 28th place. Greece ranks 31st. And Italy is not much criticized, Hungary is. Another index: Hungary ranks 89th in the World Press Freedom Index ranking. That’s low, but it is just after Israel.

All in all I got the impression that there is more to it than only the degree of democracy. Otherwise the fierceness and one-sided attention for Hungary cannot be understood. What’s going on? For an answer we need to go back history.

It was so beautiful!

While the Russians are still in the country, in 1989 Victor Orbán gives a speech at the Heroes’ Square in Budapest (see the excerpt from the Dutch IKON documentary below). He asks the Russians to leave the country. If you know the history of Central Europe, you might realize that it takes a lot of courage to act like this. He thus became a hero to many Hungarians at that time.

Sovereignty essential

With this brief retrospective, the statement Orbán made during the EU summit last summer towards the Dutch Prime Minister Rutte might be better understood. Rutte wanted to make financial support for Hungary dependent on the rule of law. Orbán responds: “These guys who inherited freedom, rule of law and political democracy did not have the experience that he and others in Eastern Europe had fighting against communism”.

The Hungarians had to fight for self-determination and freedom in 1956 and for the past 30 years. My impression is that freedom and sovereignty as a nation is higher on the Hungarian agenda than freedom as an individual. To say it simple: safety first.

INTERMEZZO in the three perspectives.

History: in 1989, as in 1956 during the Hungarian uprising, Hungarians were courageous in fighting for their freedom. Sovereignty as a nation seems the number one priority. Safety first.

Relation: Hungary claims an equal relation because of their recent fight for freedom. And demands respect.

Undercurrent: Many Hungarians are proud of considering themselves as freedom fighters. It is a part of their identity.

The liberal model is superior

The revolution of 1989 was almost without violence. This is a major achievement. But there are also disadvantages that I will come back to later. Many in Central Europe and in the West were happy. It is symbolic of Western thinking at that time that Fukayama wrote ’the End of History’. The Western liberal model would conquer the whole world.

The Western model seemed superior

At the time of the commemoration of the fall of the Wall last year, many reflected on the fall of the Wall and the development that followed. Striking in those reflections? Many people in the West as well as people in Central Europe are disappointed. In the West because a number of Central European countries have embarked on a course that we in the West don’t like. In Central Europe because the economic shock therapy and the neoliberal ideology has led to much suffering. Especially for the less fortunate.

And the Central European countries began to feel the dominance of Western Europe through the EU. While making my documentary “A Life in Hungary“, I discovered that Hungary is looking for its own roots. And Hungary is now choosing its own political course. Do we in Western Europe sufficiently understand this history and the reasons for this change?

Hungary poorly understood

“A ‘caricature’ is made of life in Eastern European countries on the basis of the ‘evil spirits’ Orbán in Hungary and Kaszynski in Poland”, De Volkskrant quotes Sylvie Kauffman (Le Monde). “Who are we to judge? We have supplied the model. For a long time it proved valuable. But even before Orbán’s rise, weaknesses emerged from the devastating crisis of 2008. That neoliberal model has failed and has also brought Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Matteo Salvini to power” according to Sylvie Kauffman.

Philippe Gélie writes in Le Figaro that the West is disappointed in the Central European countries of the EU. This disappointment is due to the West itself, to its “ideological arrogance, the naive belief in the superiority of the liberal model”.

“Why are we always on the agenda?”

This may all be the case, but why is Hungary regularly put in the dock? Or as Judith Varga, the Hungarian Minister of Justice, exclaims in a meeting at De Balie in Amsterdam I attended: “why are we always on the agenda?”. This is after she is put in the dock by the other three participants including the historical scientist and the moderator himself.

The podcast “Betrouwbare Bronnen” (“Reliable Sources”) gives a more balanced picture of the context of Hungarian politics. It contains an interview with Judith Varga (the podcast is in Dutch, but the interview with Judith Varga in English).

Undercurrent in the relationship

So Hungary always in the dock. I have a strong feeling that this has to do with what is called “the relational level” in communication theory. Communication theory distinguishes between the content level of communication and the relational level (metacommunication). The latter has to do with the relationship the parties perceive with each other and try to communicate non-verbally. Do you perceive yourself as ‘equal’ or as ‘above’ or ‘below’ the other party? And what is the perception of the relation by the other party?

Conflicts are often fought at the content level. Often in vain because the most serious conflicts usually take place at the relational level. I strongly suspect that there is an undercurrent in the relationship between Western and Central Europe that is determined by the relational level. And I’m going to explain why.

The relational level: humiliated

I have Hungarian friends that I have come to experience as my second family. Some are Orbán supporters and I am not. When I met them, we had a talk about the EU at the table. At one point the lady of the house says, “That’s your view. We have another view”. And: “You are a liberal”. While I thought that liberal values are universal, she said that she and her husband are really not “liberals.” Then we continued talking about the EU. And a little later in the conversation I give them back my feeling. “So you have the feeling being colonized?” I say. “Well, uh, yes, that’s pretty much the feeling”. The feeling of being colonized. While I thought being part of the EU is a blessing….. An eye opener to me at that time.

“You can’t force us to be what we don’t want to be.”

Caroline de Gruyter writes in her column “The humiliated Hungarians” about the French journalist Marion Van Renterghem. This journalist is visiting her old boss, Lászlo Trócsányi. He runs a law firm in Budapest. She confronts Trócsányi with at all the criticism there is of Hungary. His response?

First, he lists all the foreign dominions that Hungarians have been suffering from: the Habsburgs, Nazis and Soviets till now, as the only Hungarian-speaking country in Europe. Then he tells how often Hungary feels humiliated in the EU. Among other things, the celebration of the expansion with ten new countries in 2004, on the Grand-Place in Brussels: the fifteen “old” member states were nowhere to be seen. Nobody had come. Only with the mayor of Brussels did the ten ambassadors sing the European national anthem.

And all those contracts with Western companies that they had worked on together were stranglehold contracts. Hungarian municipalities signed, out of weakness. The arrogant French refused to revise them, even later.

“We have a misunderstanding about identity, Marion. (…) You can’t force us to be what we don’t want to be.” The conversation remains amicable. But “we are in circles, Lászlo and I” Marion Van Renterghem writes.

Caroline de Gruyter sighs in her column: whether we should not even try a little harder to help Central and Eastern Europe to get rid of that hurt feeling, that feeling of humiliation.

Imitation of the West

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, everything was liberalism that hit the clock in Europe, says the Bulgarian political scientist Krastev. For former communist countries in Europe, this meant that they were now going to imitate the West, the sole “owner” of the capitalist model. “After 1989″, Krastev said, “the world was divided into imitators and imitators.“

Initially, the imitators wanted that themselves. Eastern European dissidents always said they only wanted one thing: to get “normal” again, just like other European countries. But now, Krastev says, the imitators are revolting. Not against capitalism, but against imitation. And against the fact that they are constantly monitored by their own model. They discover that you never become more than an inferior copy of a superior model.

On an equal level

The Hungarian member of the European Parlement Schöpflin indicates that the Treaty of Trianon of 1920 already gave Hungary the feeling of walking on the leash of the West. This is what Casper Thomas writes in ‘De Autoritaire Verleiding’ (‘The Authoritarian Temptation’). As a result of the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary loses 2/3 of its territory, leaving more than 3 million Hungarians in neighboring countries. This treaty also completely disrupted the economic infrastructure.

Hungary and Poland are now choosing their own course. In terms of communication theory: they want to position themselves on an equal level with the Western European countries and within the EU. While the Western European countries still believe themselves to be superior with their liberalism.

Hungary chooses its own course

What is that own course? To put it bluntly, Hungary opts for democracy but not for (neo)liberalism. There is a good reason for that. Neoliberalism brought many Hungarian citizens to the brink of collapse. Privatized companies for gas, water and electricity generated prohibitively high bills for citizens. Mortgages based on foreign exchange made housing costs no longer bearable.

Orbán intervenes and forces companies for gas, water and electricity to lower the tariffs from 2013. He forces foreign banks to negotiate mortgages. For many households, this relief meant the difference between staying afloat or drowning, Dzsingisz Gábor writes.

INTERMEZZO in three perspectives.

History: The Treaty of Trianon (1920) gave Hungary the feeling of walking on the leash of the West. In 1989 Hungary had no choice but accepting the Western model. Again on the leash. After the financial crisis the neoliberal model brought many of the Hungarians to the edge of the abyss. And now Hungary chooses its own model: an illiberal economic and cultural model.

Relation: Western Europe dominated Hungary. Hungary was in a stranglehold. When Hungary got in trouble after the financial crisis Western Europe (ECB) didn’t help and had to go to the IMF. Western Europe didn’t pay attention. Now Hungary is revolting.

Undercurrent: Hungary feels humiliated. And not taken seriously.

Basic question: can a democracy be illiberal?

Casper Thomas in ‘The Authoritarian Temptation’: half a century of politics in the West has forged liberalism and democracy into a seemingly indivisible unity. Hungary opts for democracy but no longer for (neo)liberalism. For West Europeans quite difficult to comprehend.

According to political scientist Yasha Mounk issues such as freedom of expression, participation, rights for minorities are concepts that have become implicitly linked to democracy. But he argues that they do not belong to what democracy is at its core: a set of binding institutions that ensure that the opinion of the people is translated into policy. Liberal democracy, according to the Financal Times columnist Martin Wolf, is “a combination of universal suffrage and entrenched civil and personal rights.” “Illiberal democracy” then is, mutatis mutandis, “the combination of universal suffrage with limited rights”, according to Casper Thomas.

Values

Values are often hidden in the undertow. But what are the underlying values of that own course of the Hungarian regime? While in Western Europe liberal values predominate, the Hungarian regime opts for conservative values such as putting the family and Christian faith at the core.

Both Hungary and Poland got into trouble with Brussels because of the constitution. Regarding the latter, the respected English sociologist Frank Furedi, who is Hungarian by birth, says: “The objection was that Christianity was mentioned in the preamble to the Hungarian constitution. Here, too, different standards are used. Hungary does not have a state religion, like England does. Or Denmark, or Malta. That preamble is a statement about national history, about the origins of Hungary and what it means to be Hungarian. It is an attempt to create something of national symbolism, and I find that understandable, because in the Stalin era everything related to the nation was ridiculed. “

Soul

In my documentary ‘A Life in Hungary’ I discover that Hungary is trying to recover its soul. Sovereignty and the quest for where Hungary comes from are important for many Hungarians.

András Lanczi, a political philosopher and the rector of Corvenius University in Budapest, tells to Casper Thomas: ‘From a European perspective, the past twenty-five years have been about joining the EU, but many Hungarians it was all about the slow rediscovery of our own roots’. He describes liberal democracy as a borrowed coat that was put around Hungary’s shoulders, but actually did not fit well. “What is our shared identity? What keeps the Hungarian community together? Liberalism did not answer these kinds of questions.”

Measure with two measures

In the West, Hungary is regularly put in the dock. Partly because in Hungary politics exerts influence on the judiciary. The respected sociologist Frank Furedi, resident in England and an advocate of free speech: “There is no doubt that the Fidesz government, like its predecessor, has made efforts to influence the composition of the court [Constitutional Court]. Regrettable as it may be, the Hungarians are certainly not unique in this. Most American presidents have tried to influence the composition of the Supreme Court. President Obama did it, his successor Trump is no different. “

Why

“So the question is why political interference with the judiciary sometimes passes unnoticed, while in other cases there are rather hysterical shouting about a threat to justice,” said Frank Furedi.

He continues: “There are laws in Hungary that I don’t like, such as the abortion law, or the media law, or the education law. But I don’t see how that goes against European values. Hungary is a secular society. There is equality before the law. People are not just arrested. Dissenting opinions are tolerated, although it is clear that the government wants to have dominant influence. Like all other governments… “. Frank Furedi’s view on the Hungarian democracy, a democracy that has existed for only 30 years.

Underground struggle against former communists

Now it is a good moment to return to the revolution of 1989 and its impact. My Hungarian friends indicated 8 years ago that there are still old communists in various sections of the Hungarian society. These are the people who have brought almost a million Hungarians (!) to trial in the past. The 1991 revolution was nonviolent, a Velvet Revolution. Great. Disadvantage: these criminals are still walking around with impunity. And the Fidesz government is trying to influence the electoral system and the composition of the judiciary in such a way that the old communists do not come to power. This is the paradox the government has to deal with.

I was told by Dzsingisz Gabor that the power struggle between the former communists and the Fidesz supporters is in the undercurrent of the European Parliament. The Sargentini report is said to have come about under the influence of the old communists.

Living in a post-communist society

What it’s like to live in a post-communist society should not be underestimated. This was the message of Dzsingisz Gabor at my event (listen to my podcast with my interview with him, it is in Dutch). To be aware of the characteristics of post-communist society is crucial for a good understanding of the dynamics of Hungarian politics. Unfortunately, Western journalists never actually consider what is going on beneath the surface in Hungary.

INTERMEZZO in the three perspectives:

History: Hungary, which has a feudal tradition, is a democracy for only 30 years now. The Netherlands for example are a democracy for more than 150 years. Building a democracy in Hungary is complicated because the former criminals from the socialist era were not condemned in 1989 (a demand of the Sovjet Union). So the electoral system and the judiciary had to be influenced to keep them out in order to preserve the democracy. An intricate balancing act.

Relation: Hungary takes an independent course and develops its own form of democracy. At the same time Hungary regularly is put in the dock by West European countries.

Undercurrent: Soul-searching, looking for own roots. In order to get more self esteem. Motivation to fight for own position.

So, what’s the overall picture?

To return to Philippe Gélie: the West is disappointed in the Central European countries of the EU.

Although the Hungarian government tries to influence the judiciary and the press, Hungary is still a democracy. At least ‘partly’. However, Hungary does not opt for liberal values but for conservative values. Hungarians try to regain their roots and self-esteem. Many Western Europeans do not like this. They thought they knew what’s good for the Central European countries.

From a communication point of view: it is not so much about the content, but about the nature of the mutual relationship between Hungary and Western Europe. After 1991, Western Europe was leading. Something many Hungarians don’t want anymore. My conclusion: they choose for sovereignty (safety as a nation) and their own course. Something Western politicians and mainstream media dislike. It is a major reason why the Hungarians are regularly put in the dock. As you can feel: many different thoughts and emotions in the undercurrent. It makes the relationship in the EU between Hungary and West European countries troublesome.

My call

We must remain critical of democracy and freedom of the press in the EU countries. At the same time, it is important in relationships to have respect for each other’s history and backgrounds. And to accept that each country may also follow its own course. Treat each other as equals and utilize diversity in the unity that the EU is.

Epilogue

I would like to thank my friend and documentary maker Paul van de Wildenberg for his critical feedback. He has regularly helped students in Central and Eastern Europe to make films. I also want to thank Dzsingisz Gabor for his support and reading this article.